April 2022

Theileria, the Emerging Bovine Blood-Borne Disease?

By Dr. Gregg Hanzlicek

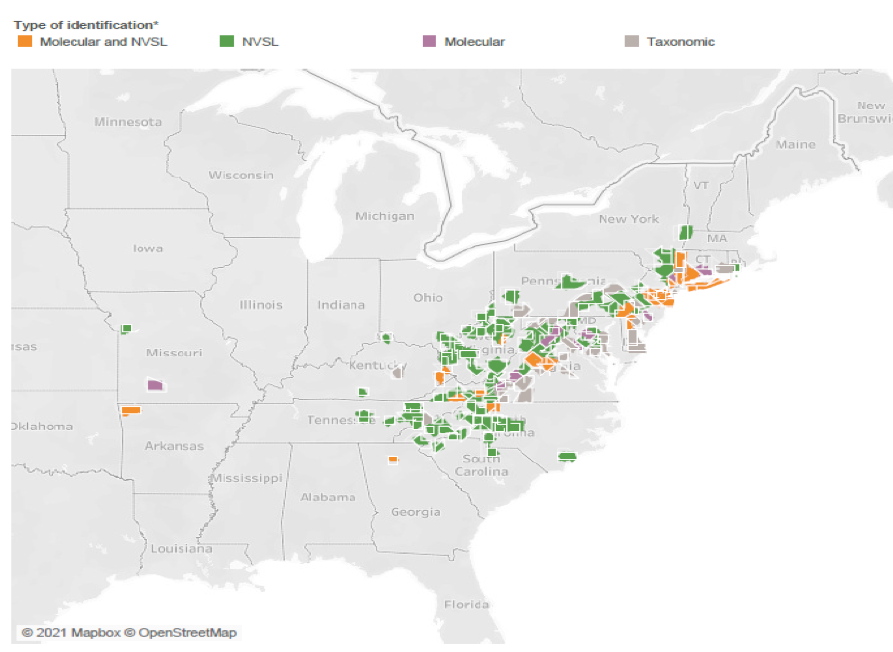

The Asian longhorned tick (also called the cattle, bush, East Asian, or scrub tick) or Haemaphysalis longicornis, has become established in the U.S. (Figure 1). Originally found in 2017, this tick has now been found in 18 states, not including Kansas (Figure 2). It has, however, been reported in western Arkansas and Missouri.

|

| Figure 1 |

The longhorned tick can be found on most domestic animals including dogs, cats, horses, cattle, sheep, and goats, and on a variety of wild animals including cervids, several bird species, raccoons, and opossums. This tick is somewhat unique because it is parthenogenetic, and the females can produce large numbers of offspring in the absence of male ticks.

Longhorned ticks are not believed to be a carrier of Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease), Anaplasma marginale (Bovine anaplasmosis), or Anaplasma phagocytophilum (Canine anaplasmosis). Experimentally, but not naturally, this tick has been known to carry Rickettsia rickettsia (Rocky Mountain spotted fever).

The primary concern with the establishment of longhorned ticks is their role as the carrier of Theileria orientalis (Theileriosis) in cattle. All other known U.S. tick species are not known to carry T. orientalis, although some researchers believe black flies, sucking lice, and needles can transmit this disease. There are eleven T. orientalis genotypes in the U.S. and the rest of the world. Of those, only Ikeda and Chitose are considered to be pathogenic in cattle.

Theileria sporozoites produced by the female are transmitted during blood feeding to the host animal where lymphoid cells are immediately infected. Although they infect cells, Ikeda and Chitose genotypes are not known to have any negative effect. In advanced Theileria stages, red blood cells are infected and destroyed, which is responsible for the typical clinical signs. Anemia, abortion, fever, and weakness are typical clinical signs of acute infection (similar to A. marginale). Most animals recover and become life-long carriers. Clinical signs can reoccur in carriers during times of stress such as late gestation, lactation, and transport.

|

| Figure 2 |

One of the most striking differences between A. marginale and T. orientalis is the difference in clinical signs due to age-of-onset. A. marginale clinical signs are typically only observed in aged adults. Severe levels of morbidity and mortality have been often reported in Theileria-infected calves as young as six to 14 weeks of age. Another difference concerns Theileriosis treatment: unlike A. marginale, oxytetracyline effectiveness is inconsistent in Theileria cases.

Nonpathogenic Theileria genotypes have been found in U.S. cattle; it is important to distinguish pathogenic from nonpathogenic types during surveillance or case work-ups. KSVDL has a PCR panel that targets the two pathogenic Theileria genotypes (Ikeda and Chitose), in addition to Anaplasma marginale and Anaplasma phagocytophilum. This panel would be appropriate when investigating both acute and carrier cases. The appropriate sample is 1.0 ml of whole blood (purple top tube).

If you have questions, please contact KSVDL Client Care at clientcare@vet.k-state.edu or 866-512-5650.