A Herd Outbreak of Equine Strangles

By Drs. Laurie Beard, Maureen Sutter, and Mike Moore

Equine Strangles is a disease most often observed in young horses 1-5 years of age, but can affect all horses. The etiological agent Streptococcus equi subspecies equi (or S. equi) is NOT a normal inhabitant of the equine upper respiratory tract. The S. equi organism is either inhaled or ingested after direct contact with mucopurulent discharges from affected horses or from contaminated equipment1. The American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine consensus statement from 2005 has reliable information for diagnosing the disease and managing outbreaks as well as stating the importance of identifying carrier horses. A severe strangles outbreak occurred in 2017 in Kansas, which resulted in many horses being ill, several horses having to be euthanized due to significant complications, and significant cost in medical bills for horse owners and owner of the stable.

History: In January of 2017 a stable housing 48 horses experienced an outbreak of strangles. These horses ranged from 6 to 36 years of age. A clinically normal horse from a sale barn had been introduced into this herd 4-5 weeks before clinical signs began to appear in the herd. In the middle of January one horse was hospitalized that was anorexic and lethargic. While hospitalized, this horse was diagnosed with coronavirus via a fecal sample. Right after this diagnosis, multiple other horses spiked with fevers and were likely also infected with coronavirus, but within one week multiple horses developed submandibular abscesses, and culture confirmed S. equi.

Clinical signs: Signs varied in this group of mature horses from none to very severe. There were a total of 31 of the 48 horses that some degree of clinical signs during this outbreak (64%). Clinical signs for the majority of horses included lymph node abscessation and/or purulent nasal discharge. There were some horses which just developed fever and/or anorexia. Four horses developed significant complications and were euthanized. This included infarctive purpura hemorrhagica (1), abdominal metastatic abscess (1), pleuropneumonia (1), and prolonged dysphagia (1).

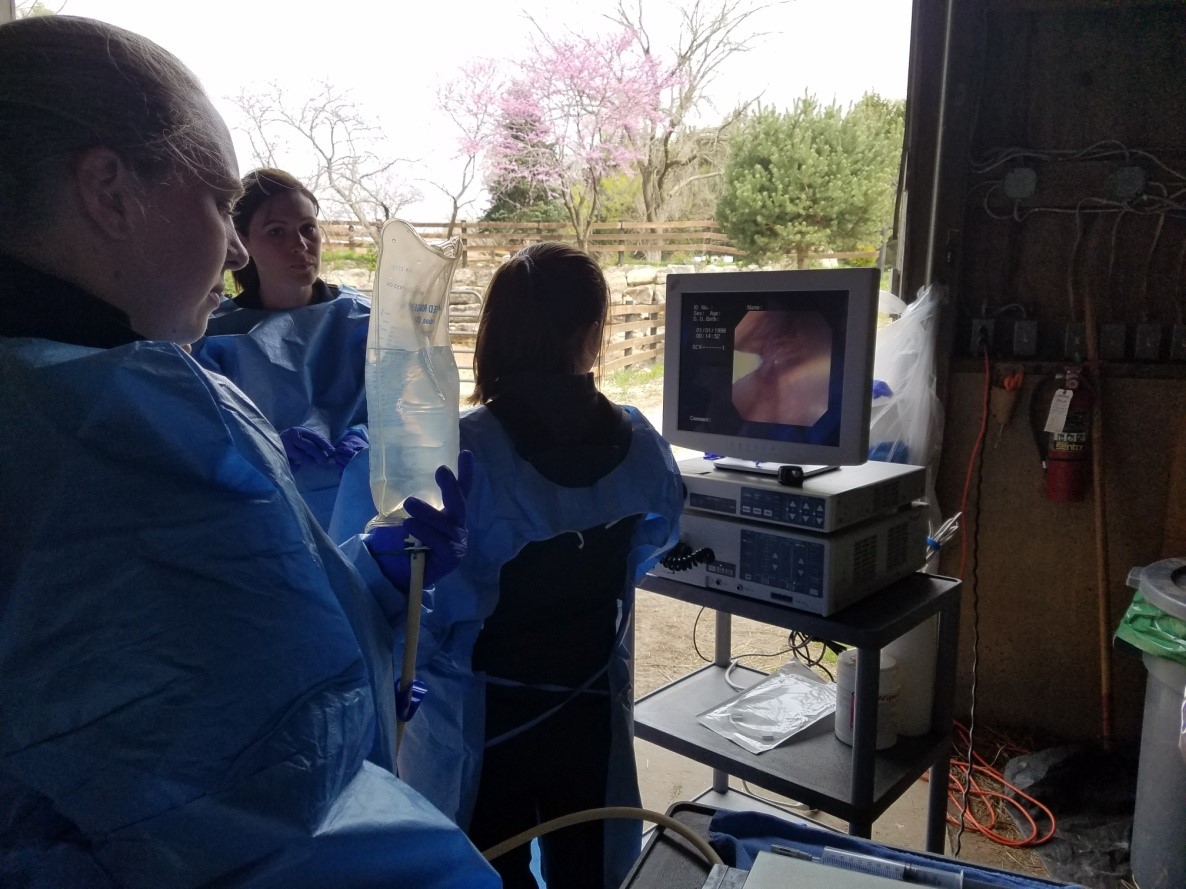

Diagnostics: Temperatures and clinical signs were monitored by owners as well as the barn owner. Fevers were no longer identified by 3/6/17. Three weeks after fevers stopped and resolution of all clinical signs (March 30th) diagnostic testing to determine if horses were free from S. equi. Diagnostic tests included nasopharyngeal washes on 17 horses (Figures 4 and 5) and endoscopic evaluation of the guttural pouches on 16 horses (Figures 1, 2, and 3). Samples were submitted for culture and PCR were performed. 15 horses were still considered infected with S. equi. This included 4 horses with guttural pouch empyema (Figure 1), 10 horses that were PCR positive but culture negative, and 1 horses PCR negative, but culture positive for S. equi.

Two weeks later, April 12th, the positives from this group were sampled again with 10 out of 13 remaining positive. Three horses had empyema or chondroids, and 7 horses were PCR positive but culture negative for S. equi. The third round of testing was done three weeks later on May 3rd. The 10 positives were sampled with only 3 remaining positive (1 with chondroids, and 2 horses PCR positive, but culture negative). After 5 months (20 weeks) the herd was finally considered clean.

Outcome: Once the disease was confirmed, the herd was closed from any horses entering or exiting the site until horses were negative by PCR and culture. This process took 5 months. The disease process was severe enough in 4 cases to require euthanasia.

Take home messages from this case: Strangles is most commonly spread by horses harboring the organism in their guttural pouch. It is important to test horses following an outbreak to prevent further spread of this frustrating disease. Testing recommendations for carrier horses include repeated (3) nasopharyngeal washes or guttural pouch lavage (considered the best place to sample from and only 1 wash is necessary). Samples should be submitted for culture and PCR for S. equi, as this organism can be difficult to culture. Prevention of bringing strangles into the herd, can also be accomplished by quarantining any new additions to a herd for four weeks and then testing (nasopharyngeal or guttural pouch lavage).

There is a vaccination for S. equi, however, the vaccine does not completely provide protection in all horses, but may reduce clinical signs. In addition, the S. equi vaccine also has increased risk of an adverse reaction when compared to other vaccinations. Purpura hemorrhagica is a severe immune mediated disease that is either associated with the disease or vaccination. Serum can be tested for antibody concentrations to the S. equi M-protein. If the titer is elevated (> 1:1,600 or higher), there is an increased risk for purpura hemorrhagica. The intranasal vaccine is a modified live vaccine and ideally it should be administered by a veterinarian. When this vaccine is administered, other vaccines (or injections) should not be administered on the same day (as abscesses at other injection sites are reported).

For a video on how to do a pharyngeal wash go to: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=78&v=gHm2lWEuQmo

|

|

|

|

Clinical signs/outcomes of the 31 infected horses: |

Figure 1 |

|

|

|

Figure 2 |

Figure 3 |

|

|

| Figure 4 | Figure 5 |

For a video on how to do a pharyngeal wash go to: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=78&v=gHm2lWEuQmo

Reference:

- ACVIM Conensus Statement: Streptococcus equi Infections in Horses: Guidelines for Treatment,Control, and Prevention of Strangles. J Vet Intern Med 2005;19:123–134